HORMONAL REGULATION OF METAMORPHOSIS IN INSECTS

A hormone is a synthetic sign sent from cells in a single aspect of a living being to cells in another part (or parts) of a similar person. They are regularly viewed as compound couriers. Albeit normally created in minuscule amounts, hormones may cause significant changes in their objective cells. Their impact might be stimulatory or inhibitory. At times, a solitary hormone may have various targets and cause various impacts in each target. There are at any rate four classifications of hormone-creating cells in a bug’s body:

Endocrine organs – secretary structures adjusted solely for creating hormones and delivering them into the circulatory framework.

Neurohemal organs – like organs, however they store their secretary item in a unique chamber until invigorated to deliver it by a sign from the sensory system (or another hormone).

Neurosecretory cells – particular nerve cells (neurons) that react to incitement by creating and discharging explicit synthetic couriers. Practically, they fill in as a connection between the sensory system and the endocrine framework

Inner organs – hormone-creating cells are related with various organs of the body, including the ovaries and testicles, the fat body, and parts of the stomach related framework.

Together, these hormone-emitting structures structure an endocrine framework that looks after homeostasis, facilitate conduct, and manage development, improvement, and other physiological exercises.

In bugs, the biggest and most evident endocrine organs are found in the prothorax, simply behind the head. These prothoracic organs fabricate ecdysteroids, a gathering of intently related steroid hormones (counting ecdysone) that animate amalgamation of chitin and protein in epidermal cells and trigger a course of physiological functions that comes full circle in shedding. Hence, the ecdysteroids are regularly called “shedding hormones”. When a bug arrives at the grown-up stage, its prothoracic organs decay (wilt away) and it will never shed again.

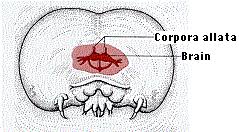

Prothoracic organs produce and delivery ecdysteroids simply after they have been animated by another synthetic courier, prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH for short). This compound is a peptide hormone emitted by the corpora cardiaca, a couple of neurohemal organs situated on the dividers of the aorta simply behind the cerebrum. The corpora cardiaca discharge their store of PTTH simply after they get a sign from neurosecretory cells in the mind.

As it were, they go about as sign intensifiers – conveying a major beat of hormone to the body in light of a little message from the mind.

The corpora allata, another pair of neurohemal organs, lie simply behind the corpora cardiaca. They fabricate adolescent hormone (JH for short), an exacerbate that represses improvement of grown-up attributes during the juvenile stages and advances sexual development during the grown-up stage. Neurosecretory cells in the mind direct movement of the corpora allata – animating them to create JH during larval or nymphal instars, restraining them during the change to adulthood, and reactivating them once the grown-up is prepared for generation. The substance structure of adolescent hormone is fairly strange: it is a sesquiterpene compound – more like protective synthetics found in pine trees than to some other creature hormone.

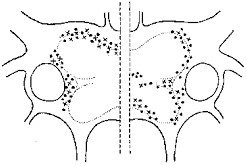

The neurosecretory cells are found in groups, both medially and along the side in the creepy crawly’s cerebrum. Axons from these cells can be followed along minuscule nerves that hurry to the corpora cardiaca and corpora allata. The cells deliver and discharge cerebrum hormone, a low-atomic weight peptide that seems, by all accounts, to be equivalent to (or fundamentally the same as) prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) fabricated by the corpora cardiaca.

Bug physiologists speculate that mind hormone is bound to a bigger transporter protein while it is inside the neurosecretory cell, and some accept that each bunch of cells may deliver upwards of three distinctive cerebrum hormones (or hormone-transporter mixes). Huge quantities of neurosecretory cells additionally happen in the ventral ganglia of the nerve string, however their capacity is obscure.

At the point when a juvenile creepy crawly has developed adequately to require a bigger exoskeleton, tactile contribution from the body enacts certain neurosecretory cells in the cerebrum. These neurons react by discharging cerebrum hormone which triggers the corpora cardiaca to deliver their store of prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) into the circulatory framework.

This unexpected “beat” of PTTH animates the prothoracic organs to emit shedding hormone (ecdysteroids). Shedding hormone influences numerous cells all through the body, yet its rule work is to animate a progression of physiological functions (all in all known as apolysis) that lead to union of another exoskeleton.Many different tissues and organs of the body likewise produce hormones.

Ovaries and testicles, for instance, produce gonadal hormones that have been appeared to organize romance and mating practices. Ventral ganglia in the sensory system produce one compound (eclosion hormone) that enables a creepy crawly to shed its old exoskeleton and another compound (bursicon) that causes solidifying and tanning of the upgraded one. There are then again different hormones that control the degree of sugar broke down in the blood, change salt and water balance, and direct protein digestion.

During this cycle, the new exoskeleton structures as a delicate, wrinkled layer underneath the hard parts (exocuticle in addition to epicuticle) of the old exoskeleton. The length of apolysis goes from days to weeks, contingent upon the species and its trademark development rate. When new exoskeleton has framed, the bug is prepared to shed what’s left of its old exoskeleton. At this stage, the creepy crawly is supposed to be pharate, implying that the body is secured by two layers of exoskeleton.

However long ecdysteroid levels stay over a basic limit in the hemolymph, other endocrine structures stay inert (hindered). Be that as it may, at the finish of apolysis, ecdysteroid fixation falls, and neurosecretory cells in the ventral ganglia start discharging eclosion hormone. This hormone triggers ecdysis, the physical cycle of shedding the old exoskeleton.

Likewise, a rising convergence of eclosion hormone animates other neurosecretory cells in the ventral ganglia to emit bursicon, a hormone that causes solidifying and obscuring of the integument (tanning) because of the arrangement of quinone cross-linkages in the exocuticle (sclerotization).

In youthful bugs, adolescent hormone is discharged by the corpora allata before each shed. This hormone restrains the qualities that advance improvement of grown-up attributes (for example wings, conceptive organs, and outside genitalia), making the creepy crawly stay “youthful” (fairy or hatchling).

The corpora allata become decayed (recoil) during the last larval or nymphal instar and quit delivering adolescent hormone. This deliveries restraint on advancement of grown-up structures and makes the bug shed into a grown-up (hemimetabolous) or a pupa (holometabolous).

At the methodology of sexual development in the grown-up stage, cerebrum neurosecretory cells discharge a mind hormone that “reactivates” the corpora allata, invigorating reestablished creation of adolescent hormone. In grown-up females, adolescent hormone invigorates creation of yolk for the eggs. In grown-up guys, it invigorates the extra organs to deliver proteins required for fundamental liquid and the instance of the spermatophore. Without ordinary adolescent hormone creation, the grown-up remains explicitly sterile.

In spite of the fact that the part of hormones in the physiology of shedding was first depicted by V. B. Wigglesworth in the 1930’s, there is still much about the cycle that we don’t completely comprehend. Bug endocrinology is right now a functioning region of exploration since it offers the potential for disturbing the existence pattern of a nuisance without mischief to the climate.

Interesting